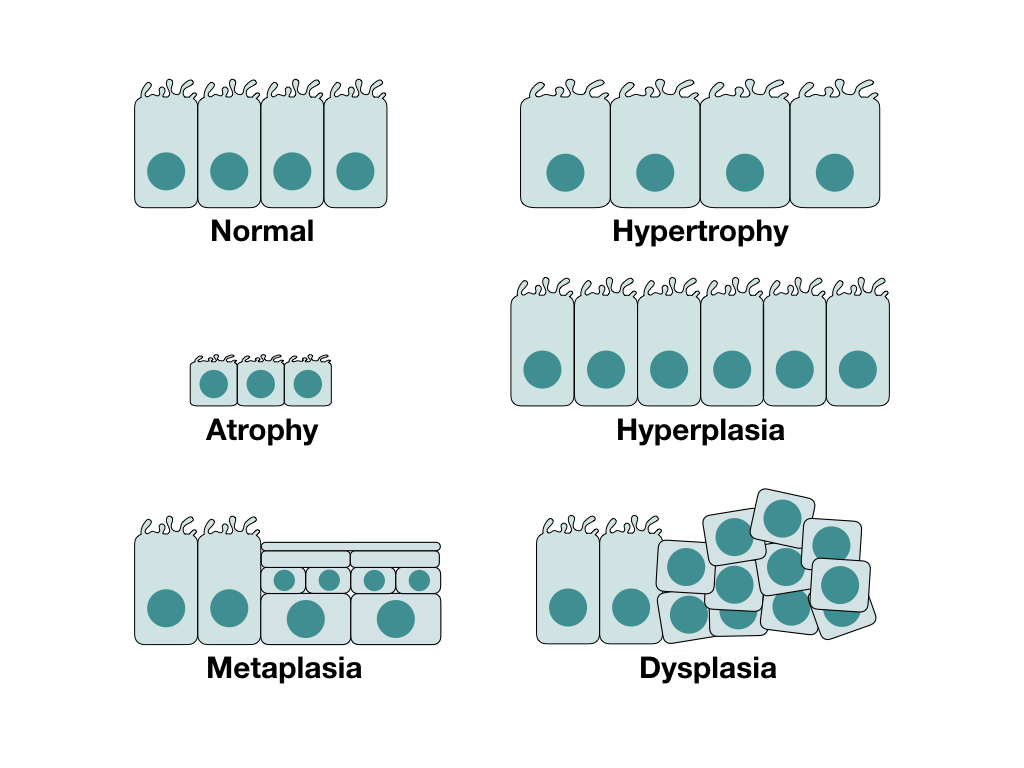

Chronic injury can affect the number, size and appearance of cells, depending on the type of injury and the cells affected. These changes can either help the cells resist injury by increasing their function, or put the cell in a diminished functional state that prevents cell death. The major changes are hypertrophy, hyperplasia, atrophy, metaplasia and dysplasia.

Hypertrophy

Hypertrophy is an increase in the size of a cell due to an increase in the size or number of organelles. Thus, hypertrophy is distinguished from cell swelling or accumulation of substances, since these conditions that also increase cell size do not affect the organelle density. Hypertrophy can occur in any cell, and typically occurs in response to increased workload. A good example of this is cardiac muscle hypertrophy in response to athletic training.

Hypertrophy is ultimately due to increased cellular protein production. Surface cell receptors will detect an increased workload, which activates intracellular signalling pathways like PI3K/AKT or G-protein-coupled receptor pathways. These pathways increase growth factor production and activation of genes that encode protein production.

Hyperplasia

Hyperplasia is an increase in the number of cells, and can only occur in cells that are able to undergo mitosis. One of the most common cell types to undergo hyperplasia is epithelial cells, due to their high mitotic capacity. Some of the main stimulants of epithelial hyperplasia are trauma, hormonal stimulation (physiologic or pathologic) or inflammation. The critical distinction between hyperplasia and neoplasia is reversibility, such that hyperplasia will resolve if the stimulus is removed.

Hyperplasia can come from two sources: proliferation of mature cells and increased output by tissue stem cells. These proliferations are primarily driven by increased growth factors, along with other signalling pathways.

Atrophy

Atrophy refers to a decrease in the size of an organ or tissue either due to decreased cell size or a decreased number of cells. It is important to remember that hypoplasia is not a form of atrophy, as in hypoplasia the cells never developed in the first place. Atrophy typically occurs from decreased stimulation, either due to loss of hormonal stimulation, reduced workload or loss of nerve stimulation. It can also occur due to compression or nutrient deprivation preventing adequate cell function.

The fundamental mechanism behind atrophy is decreased protein synthesis and increased protein degradation. With decreased stimulation by things like growth factors, the cell reduces uptake of nutrients and subsequently reduces protein production. Reduced nutrient concentrations also activates ubiquitin ligases, which attach ubiquitin to cellular proteins. This allows the proteins to be targeted by proteasomes in the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway, causing them to be degraded. Atrophy may also have some component of autophagy involved.

Metaplasia

Metaplasia is a change from one cell type to another cell type with the same lineage. The classic example is squamous metaplasia, where another epithelial cell type responds to trauma by converting to a stratified squamous epithelium. Although this metaplasia helps protect against the trauma, it prevents the epithelium from carrying out its usual function. For example, metaplastic respiratory epithelium will not longer have goblet cells to produce mucus, preventing proper pathogen clearance.

Metaplasia does not affect the existing cells, it actually occurs by replacing the existing cells with new metaplastic cells. This process occurs by reprogramming local tissue stem cells, or colonization of cell populations from adjacent sites. Cytokines, growth factors and other signalling molecules trigger stem cell reprogramming by changing the differentiation pathway of these cells. Because the stem cells can be affected directly, metaplasia can lead to neoplasia in some cases.

Dysplasia

Dysplasia typically refers to abnormality in formation of a tissue, particularly during embryogenesis. However, epithelium can become dysplastic as a precursor to neoplasia. In this case, the epithelium has more poorly differentiated or immature cells that have marked atypia.

Zachary JF. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease, Sixth Edition.

Kumar V, Abbas AK, Aster JC. Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease, Tenth Edition.