Vet med loves to give two very different things the same nickname, for some reason. In this case, both of these pathogens, Cryptococcus and Cryptosporidium, share the same short name of Crypto. So what is the difference between them?

Table of Contents

Cryptococcosis

Cryptococcosis is caused by a type of fungus, Cryptococcus. Specifically, we think about the two species C. neoformans and C. gattii. These fungi primarily affect cats, but can be seen in dogs and horses as well.

Pathogenesis

Cryptococcus yeasts are found in the environment, particularly in the soil and in pigeon droppings. The animal inhales these yeasts, or they enter the animal through a contaminated wound. Depending on where the fungus sets up shop, different clinical signs develop. Perhaps the most significant extension of this fungal infection is respiratory infections extending into the meninges and neuropil of the brain, causing CNS signs.

Clinical Signs

- Upper respiratory signs including sneezing, nasal discharge, polyp-like masses in the nostrils and swelling of the bridge of the nose. These signs occur after inhalation of the fungus.

- Cutaneous lesions after contamination of a wound, such as firm nodules that may ulcerate.

- Neurologic signs like seizures, circling, paresis, blindness, depression from extension into the meninges and brain.

- Ocular signs like blindness, retinal detachment and panophthalmitis, secondary to extension into the eyes.

© Moore licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Diagnosis

Typically Cryptococcus is diagnosed on cytology of nasal secretions, skin secretions or cerebrospinal fluid. Cytology allows for direct visualization of the fungus to make the diagnosis. There is also an antigen test that can be used on serum, urine or CSF if the fungus is not identified on cytology.

© Scruggs licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Treatment

Our typical antifungals, fluconazole and itraconazole are the treatments of choice. Amphotericin B can also be used.

Cryptosporidiosis

If you were thinking “Cryptosporidium is probably a fungus too!”, well… unfortunately it’s not. Despite the name sounding very fungus-like talking about spores and stuff. Surprise! It’s actually a protozoa. There are many many many different species of Cryptosporidium, but the most significant one to think about is Cryptosporidium parvum, because it is zoonotic. In our veterinary species, it most commonly affects young calves, lambs and goats.

Pathogenesis

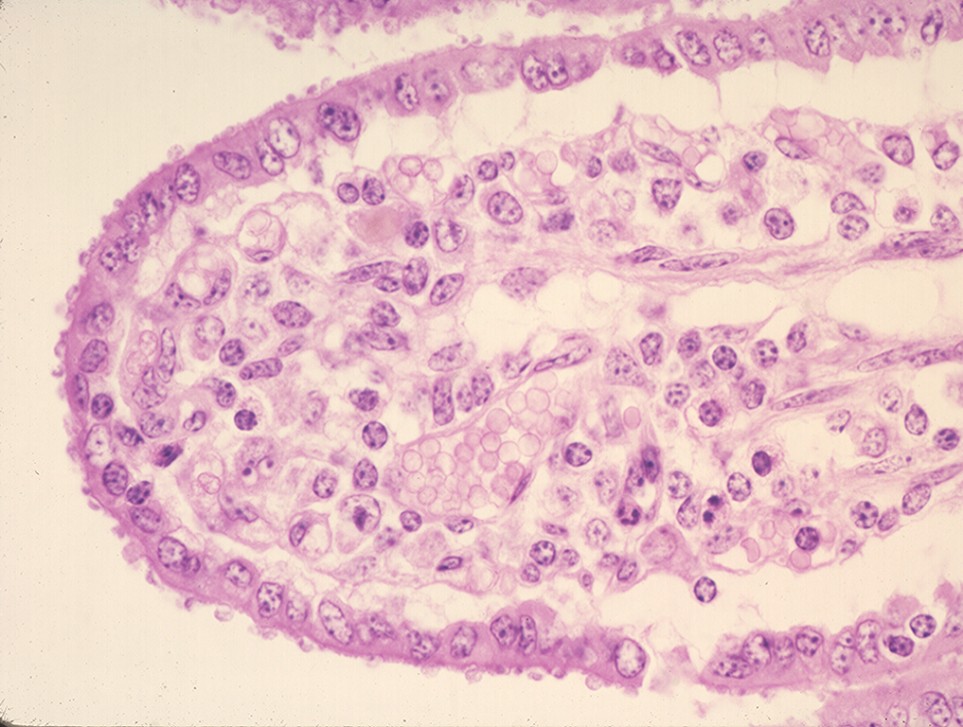

Animals infected with Cryptosporidium shed oocysts in the feces, which are already in their infective form. This allows easy fecal-oral transmission from calf-to-calf, contamination of surfaces, or even contamination of feed and water. Once the oocyst is ingested, it releases sporozoites which enter the enterocytes. Within the enterocytes, they undergo replication, and eventually lyse their enterocyte home to release more infectious organisms into the feces. This lysis process reduces the ability of the gut to absorb water and nutrients, leading to diarrhea.

Clinical Signs

- Diarrhea that lasts several days, and does not seem responsive to treatment. It often has a bright yellow colour to it. The animal may also suffer from dehydration, weakness and collapse as a result of their profound fluid loss.

© Ramos licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Diagnosis

Because the oocysts are passed in the feces, they are relatively easy to identify by observing them in a sediment from a fecal flotation. There are also PCR, ELISA, and antibody tests available.

© Dodd licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Treatment

Unfortunately, there are no approved treatment drugs (at least in Canada), however halofuginone has been used in other countries. Thus, these animals are often treated with supportive care only, including fluids and electrolytes.

Prevention

Without a targeted treatment, prevention becomes even more important! The primary prevention method is calving in a clean environment, with strict hygiene protocols. Ensuring that each calf receives adequate colostrum can also help. Finally, any calves that break with diarrhea should be immediately isolated from the herd in order to prevent further environmental contamination.

Comparison Table

| Pathogen | Type of Pathogen | Most Common Species | Clinical Signs | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cryptococcus | Fungus | Cats | Upper respiratory signs Cutaneous lesions Neurologic signs Ocular signs | Fluconazole Itraconazole |

| Cryptosporidium | Protozoa | Young calves | Profound diarrhea | Supportive care |

Check Your Understanding

Zachary JF. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease, Sixth Edition.

Taboada J. Cryptococcosis. Merck Veterinary Manual 2020.

Witola WH. Cryptosporidiosis in Animals. Merck Veterinary Manual 2021.