The body has three basic cavities: the thorax, the abdomen, and the pericardial sac. Sometimes, these cavities can become filled with various types of fluids. These accumulations can have different outcomes depending on the type of fluid, and its effects on the surrounding organs.

Table of Contents

Types of Fluids

In the land of pathology, one of the first things a pathologist might ask you about fluid in a cavity is “what type of fluid is it?” What they’re really asking is the fluid a transudate, modified transudate or an exudate. Fluids are classified into one of these categories based on their cellularity and protein.

Transudates are low cellularity, low protein fluids, that are essentially composed of the fluid component of plasma. Transudates occur from some disturbance in the normal fluid balance in a vessel (see our post on Causes of Edema). This leads to increased fluid moving out of the vessels, but through an intact endothelium (cells lining the vessel). The endothelium prevents the movement of most cells and proteins, producing a transudate. Transudates are classically translucent and have a watery appearance.

Exudates are at the opposite end of the spectrum, having high cellularity and high protein. In these fluids, the endothelium is either damaged or the endothelial cells have contracted, increasing the spaces between the cells. This allows larger molecules like cells and proteins to escape the vessels, and produces an exudate. Exudates are typically opaque, and may come in different colours depending on what the predominant cell type is. Pus and hemorrhage are examples of exudates.

Modified transudates are somewhere in between, having variable cellularity and protein. Some pathologists prefer not to use this term, since it is quite ambiguous! However you will still see it out in the literature, so it is important to mention. These types of fluids occur when there is a “normal” vessel with some pathology producing a transudate, but the fluid that leaks out has a higher protein content than normal. There are many things that can cause this, but we typically think of modified transudates when there is obstruction or damage to lymphatic drainage, or irregular development of lymphatics.

Thorax

The thorax is a fairly common site for fluid accumulation, with many different underlying causes. Identifying the type of fluid present through thoracocentesis (needle into the thorax to retrieve a fluid sample) is an important step in identifying what is going on with the patient.

Hydrothorax

Hydrothorax, literally water in the thorax, is when a transudate accumulates in the thorax. These fluids are generally clear, odorless and do not form clots when exposed to air. Hydrothorax is caused by the same mechanisms that cause edema: increased hydrostatic pressure, decreased oncotic pressure, altered vascular permeability or obstruction of lymph drainage. Typically, hydrothorax is most commonly associated with heart failure and liver disease.

© Harrington licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Hemothorax

Following along a similar naming convention as hydrothorax, hemothorax is blood in the thorax. This can range from frank blood to sanguineous exudates, or exudates tinged red due to the red blood cell component. Hemothorax can be caused by major disruptions in vessels or clotting, including vessel rupture, clotting defects or neoplasia eroding a vessel wall.

© Mosier licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

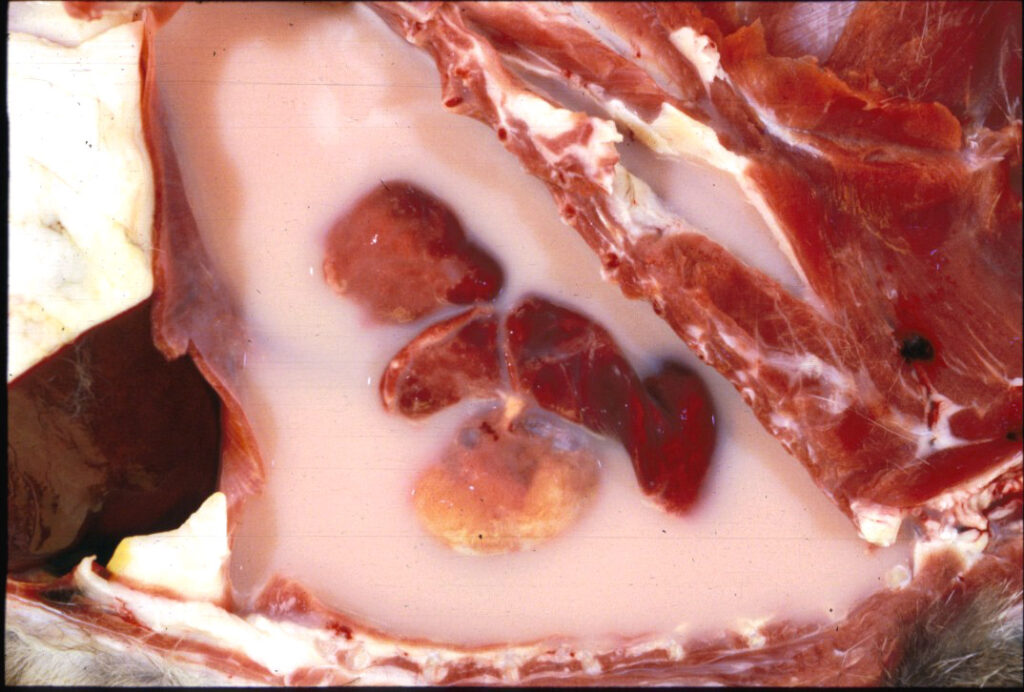

Chylothorax

Another type of exudate is chylothorax, or accumulation of lymphatic fluid in the thorax. These fluids are typically opaque and milky-looking, and may be white to pink in colour. This is because chylous fluid is high in triglycerides, the major component of fat. Chylothorax is caused by rupture of a lymph vessel, either from trauma, surgical rupture, neoplasia eroding the lymphatic wall, or inflamed lymphatics. This type of fluid is typically classified as a modified transudate.

© Hanna licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Consequences of Thoracic Fluid

When there is a large amount of fluid in the thorax, the major consequence is atelectasis from the fluid compressing the lungs. Without being able to properly inflate the lungs, these animals may show signs of respiratory distress.

Abdomen

Similar to the thorax, the type of fluid present in the abdomen can be identified by abdominocentesis.

Ascites

Just to throw a wrench in the works, watery fluid in the abdomen isn’t called hydroabdomen, it’s called ascites or hydroperitoneum. The viscosity of the fluid can be quite variable. Thin and watery ascites can be caused by heart failure, hypoproteinemia, or other causes of edema.

Highly viscous ascites can result from feline infectious peritonitis, due to fibrin accompanying the leaking fluid, making the fluid syrupy as it tries to form clots. Technically, this form of ascites is an exudate, due to the high protein content, although it is still called ascites. Sometimes in human medicine, they call this specific circumstance “exudative ascites” to clarify the type of fluid.

© Kesdangsakonwut licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

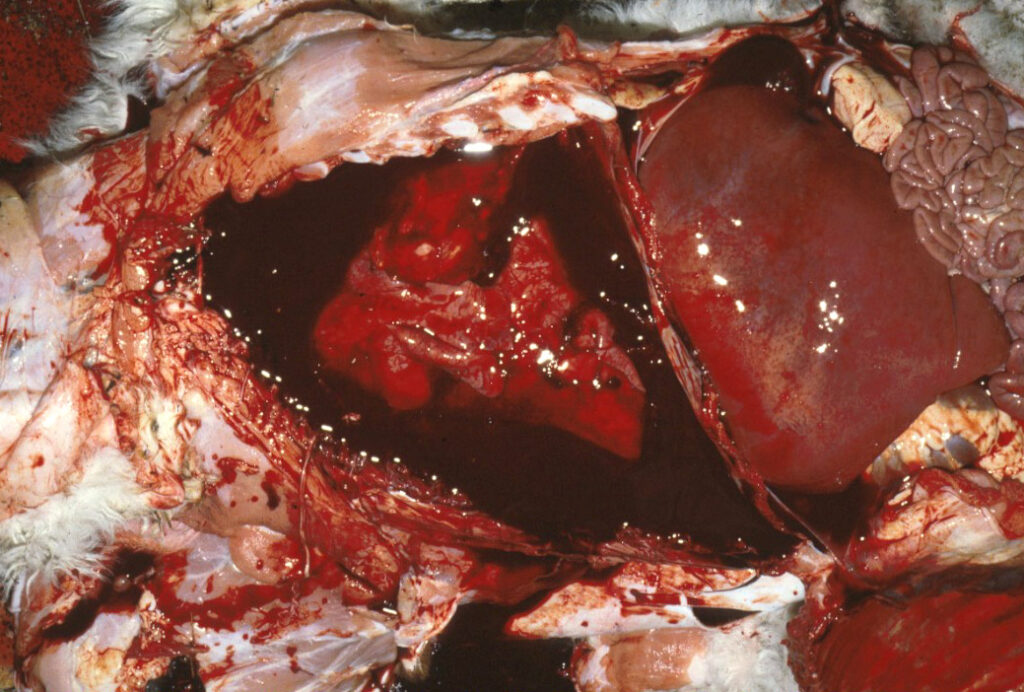

Hemoabdomen

Hemoabdomen, or hemoperitoneum, is an accumulation of blood or bloody exudate in the abdomen. Similar to hemothorax, this condition is typically caused by rupture of vessels or erosion of a vessel by a tumour (e.g. hemangiosarcoma) or inflammation. Aneurysms from parasitic infection or spontaneous formation can also rupture, leading to hemoabdomen.

© Rech licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Consequences of Abdominal Fluid

Thankfully, the organs in the abdomen are relatively resistant to increased fluid pressure. However, the abdomen is a very large space that can hold a lot of fluid. Depending on the type of fluid and its components, this could lead to hypovolemia, hypoproteinemia or anemia if a large amount of fluid is lost. Abdominal fluid gives the animals a large, distended abdominal shape, and may have a “fluid wave” if balloted. In very severe cases, the fluid may prevent diaphragm movement, leading to respiratory distress.

Pericardial Sac

Pericardial fluid is probably the most severe form of cavitary effusion, because there isn’t a lot of room in there, and the heart still needs to beat! The fluid type can be identified by pericardiocentesis.

Hydropericardium

As I’m sure you can guess, hydropericardium is watery fluid (transudate) in the pericardial sac, and is caused by anything that causes generalized edema. If hydropericardium is caused by increased vascular leakage, there may be a component of fibrin involved, producing a gelatinous, viscous exudate.

Often, ascites, hydrothorax, and hydropericardium can be seen at the same time, and is called a tricavitary effusion. This group of lesions is associated with congestive heart failure.

© Uzal licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Hemopericardium

Similar to the other cavities, hemopericardium is blood or bloody exudate in the pericardial sac. This typically results from rupture of a vessel from trauma, or rupture of the heart wall due to hemangiosarcoma.

© Rech licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Consequences of Pericardial Fluid

The consequence of pericardial fluid depends primarily on the speed at which the fluid accumulates. In the case of hydropericardium, the fluid typically accumulates quite slowly. This allows the pericardial sac time to stretch to compensate for the increased fluid. In hemopericardium, typically a large amount of fluid is released into the pericardial sac at once, which doesn’t allow time for compensation. This can result in cardiac tamponade, where the heart is physically unable to beat due to the pressure of the fluid surrounding it. This ultimately results in death for the animal.

In some cases, the animal may have an irregular ECG output called electrical alternans. In this condition, the R wave amplitude alternates between high and low, due to the swinging of the heart within the fluid-filled pericardial sac. Weird!

Comparison Table

| Type of Fluid | Protein Level | Cellularity | Causes | Consequences |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transudate | Low | Low | Increased vascular permeability Increased hydrostatic pressure Decreased intravascular osmotic pressure Decreased lymphatic drainage | Atelectasis (hydrothorax) Abdominal distention, possible hypovolemia (ascites) Electrical alternans (hydropericardium) |

| Modified Transudate | Mid-range | Mid-range | Lymphatic obstruction Lymphatic rupture Lymphangiectasia | Atelectasis (chylothorax) |

| Exudate | High | High | Vessel rupture or erosion Aneurysm Clotting dysfunction Inflammatory endothelial damage (e.g. FIP) | Atelectasis (hemothorax) Anemia, hypoproteinemia (hemoabdomen) Cardiac tamponade (hemopericardium) |

Check Your Understanding

Zachary JF. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease, Sixth Edition.

Photos © Noah’s Arkive contributors Rech, McGavin, King, Crowell, Neto, Driemeier, Saunders licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.